SARS-CoV-2. You know it best as the virus causing the current COVID-19 pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus. These viruses get their name from their appearance under a microscope – a tiny fat bubble surrounded by a crown of spikes. Scientists are still trying to figure out the source of this deadly virus. Some people say it’s from bats, others say it’s from a pangolin. But if COVID-19 did indeed come from a bat, past evidence shows it may have gone through another animal and then to humans.

Comparative immunologist and leading bat researcher Dr Michelle Baker explains.

SARS-CoV-2: a quick history lesson

Back in 2013, a horseshoe bat was caught in a trap in the Chinese province of Yunnan, about 2000 kilometers south-west of Wuhan. Scientists at the time swabbed its mouth and checked for viruses. It had a virus that had no one had seen before. It was a SARS-related coronavirus. Fortunately for scientists at the time, this new virus only infected bats. There was no evidence for human infection. The scientists named this new virus RaTG13 and left it at that.

But it’s now thought RaTG13, or another similar bat-based virus, had slightly changed its gene sequence. These minor genetic manipulations turned it from a bat-only disease to SARS-CoV-2, the one causing today’s pandemic.

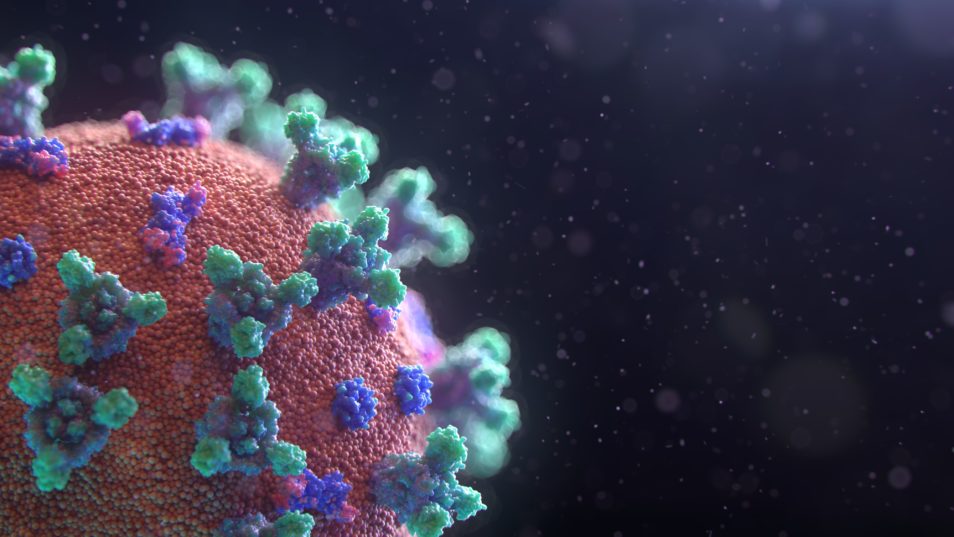

A visualisation of SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes the disease COVID-19.

Bats are central to past viral outbreaks

Bats have coexisted with viruses for a long time. These viruses are part of their microbiome and don’t cause any harm to the bats. But, they can cause adverse consequences to us if we come into contact with them.

If you cast your mind back to recent nasty viruses, almost all have a bat origin. For example, SARS, MERS, Nipah, and Hendra all came from bats.

But usually, bat viruses can’t transmit directly into humans (except for the Australian bat lyssavirus). This is because their original virus genes don’t bind as effectively with our cell’s receptors. So, there are a few missing links which allow this to happen. And that’s an intermediate host animal, and a unique set of circumstances which allow a bat to spill a virus into that intermediate host.

When two genetic mutations become one virus

Another host needs the right conditions (or cell receptors) for a bat virus to infect them.

“There is evidence of recombination between the coronaviruses,” Michelle said.

Recombination is when your DNA sequence is broken down into parts and rejoined in a different combination. This creates a new gene sequence. DNA recombination is not always bad. Humans do this during reproduction and pregnancy to allow for genetic diversity in the new embryo. But this recombination may change the virus’ signals.

“So, for example, if you have a couple of different coronaviruses which spilled over into an intermediate host, they can actually recombine. And that can increase their chances of spilling over into humans,” Michelle said.

Civet cats were the intermediate host in the 2002-2004 SARS epidemic.

The SARS example

Let’s look at one example. We know bats carry a diverse range of coronaviruses and they have a high rate of recombination. The recombination of two bat coronaviruses can result in a virus that has a higher chance of infecting another susceptible host. This is hypothesised to have been the case for the original SARS-CoV, with the resulting virus being capable of infecting civet cats and then humans.

Another example is it could have recombined with another coronavirus already there in that intermediate host. For this to occur, both viruses must be able to infect the intermediate host so recombination can happen.

We’re taking it back to coronaviruses. They have recently been identified in pangolins that share only a 90 per cent gene similarity with SARS-CoV-2. However, the region responsible for binding the ACE2 receptor which allows the virus to enter cells is 99 per cent similar to SARS-CoV-2.

In contrast, the virus identified in bats (RaTG13) is extremely different in the receptor binding region (with 77 per cent similarity). This suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 virus may be the result of a recombination between two viruses, one that is close to RaTG13 and another that is close to the pangolin virus. However, we still don’t know whether pangolins were involved in this spillover event or whether another intermediate host played a role.

The right conditions

When the bat virus spills over to another host, it becomes highly compatible with their receptors. So, it replicates to a much higher level. This increases its infectiousness. Because of this, it becomes much more likely to infect a third host – a human. But these transmissions can’t happen with what Michelle calls the “right conditions.”

“With SARS, the problem was that you had a live animal market where you had this melting pot of different species. SARS transferred from a bat into a civet cat and then into a human,” Michelle said.

“If we didn’t have those unique sets of circumstances, the virus wouldn’t have had the opportunity to spill over into another animal and then into a human.”

Dr Michelle Baker believes we should and could learn from this pandemic.

Limiting these interactions between wild animals

COVID-19 won’t be the end of these bat-to-animal-to-human viruses. If anything, they will only increase.

“There are a whole range of reasons why wild animals and humans are interacting more. It’s associated with increasing urbanisation, resulting in more interactions between humans and wildlife,” Michelle said.

“There could also be changes in climate, bats moving into urban areas to get food… it’s increasing the likelihood of virus spillover.”

But there’s no need to worry about bat to human transmission. Zoologist Dr David Wescott, who has spent 20 years researching flying foxes, said direct transmission was very rare and required intimate contact. That means handling or eating these animals, being bitten or being exposed to the disease through contact with another species that sheds high quantities of the disease. On top of that, direct exposure of the public to bats is extremely rare.

“Bats are very important members of our ecosystem, providing a broad range of services to humans. This includes consuming insect pests and dispersing pollen and seeds from trees to enable new growth,” David said.

“An effective approach to maintaining our distance from bats is to avoid all physical contact with them by not handling live or dead bats.

“Rather than ineffectually disturbing flying-fox camps, resources would be better directed towards identifying potential zoonotic diseases. This leads to the development of broad base vaccines and anti-virals to enable rapid responses.”

Michelle agrees. But she believes studying bat immune systems can give us these clues.

“I hope we can learn from this one,” she said.

16th April 2020 at 1:09 pm

Thanks for the article, could the mutations be genetically engineered please?

16th April 2020 at 11:50 am

Thank you – great to get quality information. Les

14th April 2020 at 5:10 pm

There are at least twenty thousand wildlife carers in Australia many handle a number of wildlife dead and alive and many specialize in just bats or in one or two species of native animals and have done so for 30 years or more. Apart form the Lyssavirus there does not seen to be other problems with carers contracting viruses. In hind sight I along with a number of other carers in this area of the original Lyssavirus case and a number of Hendra were the Guinea pigs for the rabbies Lyassa 1 -6 vaccination to orove the vaccination will protect us from the Lyssa 7. Around this time the toxic culture of illegal dispersals and legal and illegal land clearing causing stress and death to the bats and animal cruelty ran unchecked by the State Government in Central Queensland resulting in a rapid decline in numbers of Blacks and Little Reds and change in mating and birthing season. Now pups can come in at anytime of the year. . .

9th April 2020 at 5:47 pm

This is a most unfortunate and rather misleading article. Firstly, to get some facts straight – the possible initial host for the virus was a micro-bat, a horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus. The linkage between the bat and the virus is at best tenuous, as it appear that the linking animal is still not identified (money is on pangolins).

For some massively journalistic laziness – at least here in Australia, when the word “bat” is mentioned – we promptly get pictures of flying foxes, even when the animal is a micro-bat. I’m surprised that CSIRO should stoop this low – at least get the facts right.

In Australia (and elsewhere in the world) flying foxes are under massive attack – loss of habitat by urbanization, land clearing and outright killing, whereas micro-bats – we are largely unaware of.

Sadly most of the public have no idea of the difference between the two groups of bats. Unfortunately flying foxes (mega-bats) are large, noisy and obvious – plus they eat your fruit. In Australia, micro-bats escape notice altogether (unless one decides to roost in your curtain or dressing gown). They are primarily insect eaters (and don’t eat fruit), and are for us, silent, nocturnal and unobtrusive (and probably do massive service to agriculture by eating pest species)

Our threatened environment needs both – the flying foxes and their relatives are important pollinators of a wide range of trees, and are dispersers of a variety of seeds (think of the mango dropped on your roof). Micro-bats role is more difficult to determine (from a human perspective) – as they are quiet nocturnal operators.

However – flying foxes are directly impacted by Anthropogenic warming, with recent heat events claiming tens of thousands of animals. Flying foxes, are, like humans, slow reproducers – 1 baby per year. These heat impacts are causing major reductions in flying fox populations. Spectacled flying foxes, it is estimated, lost 25-30% of the known population in one heat event near Cairns.

We don’t know how micro-bat species are impacted.

The last thing we need is more negative publicity against bats – and it ain’t only in Australia

https://www.rte.ie/news/coronavirus/2020/0325/1126393-authorities-in-peru-prevent-bat-burning/

7th April 2020 at 5:48 pm

what are the chances of finding a suitable vaccine to cover covid 19 within 6 months

16th April 2020 at 11:54 am

Hi Terry, thanks for your message.

While there are a number of groups around the world who have developed vaccine candidates, there’s still a lot of testing that needs to be done, so 18 months is still a safe timeline.

Find out more about what’s involved in developing a vaccine here: https://blog.csiro.au/coronavirus-18-months-away-who/

Thanks,

Kashmi

Team CSIRO