ATNF News 2 | December 2023

Welcome to issue two of our ATNF newsletter for the astronomy community.

As the year draws to an end, I’d like to celebrate some of the science the ATNF has helped astronomers in Australia, and around the world, achieve.

From fast radio bursts detected and located, to mysterious stellar objects, to potential polar ring galaxies, to the hints of the fingerprints of low-frequency gravitational waves, and double pulsar eclipses, it’s been a busy year for astronomers using the instruments that make up the ATNF.

Even as new international instruments come online there remains strong demand for our ATNF telescopes and their unique capabilities. In 2022-23 we received 234 observing proposals from 1437 astronomers across 33 countries and through our merit-based selection process we are able to allocate telescope time just for the most impactful of these requests.

I also want to specifically acknowledge and say thank you to all the hard-working individuals who help to keep the Australia Telescope National Facility running in sometimes extreme conditions.

Most of all, thanks to you all for being part of our global science, research and engineering community. I wish you all a safe and happy festive season.

Dr Douglas Bock, ATNF Director

We are set to resume commissioning in early 2024 for our new CryoPAF receiver for Murriyang, our Parkes radio telescope. CryoPAF brings significant improvements in several key areas that, taken together, will help astronomers see fainter objects, survey more of the sky, and study a wider range of cosmic phenomena. The team are aiming to reinstall the upgrade for the telescope on Wiradjuri Country early next year. Stay tuned for further updates.

or over five years, our ASKAP telescope on Wajarri Yamaji Country has been a leader in the detection and localisation of fast radio bursts. Our engineers are now working hard on getting ASKAP's new transient-detecting hardware upgrade, called CRACO, ready for business.

The upgrade provides five times more sensitivity than ASKAP's existing system and uses the instrument's correlator to identify bursts, rather than the telescope's beamformers alone. CRACO uses this advancement to combine the signals from each of ASKAP's 36 antennas as if they were one highly directional antenna, increasing the detector's effective collecting area and allowing it to identify more bursts, and faster.

Shortly after the installation of CRACO the team celebrated their first fast radio burst discovery, demonstrating the bulk of the system is working.

Dr Keith Bannister, CRACO engineer and Principal Investigator for ASKAP's CRAFT survey team, says the burst named FRB231027 could be at a redshift as distant as z~1.

"The newly discovered burst has a dispersion measure of 995 pc/cm3 and has been well localised, however, it has no detectable host in public optical surveys," said Keith.

When fully operational, CRACO will make a million images every second in its hunt to find and localise fast transients. With this upgrade we’re expecting ASKAP to detect even more fainter and more distant signals, including new pulsars and higher redshift fast radio bursts – events that are orders of magnitudes older than our Solar System, enabling astronomers to learn more about the early Universe.

For the past two years, Natasha Maimbo has been one of the engineers working on the next-generation CryoPAF receiver for Murriyang, our Parkes radio telescope.

"I'm excited to see the CryoPAF receiver go to its final home, and to see how the commissioning goes," Natasha says. "This project has been a big effort from the whole team."

A mechanical engineering graduate from UTS Sydney, Natasha says she was inspired to be an engineer by the wide impact, reach, and versatility of the role.

"I knew that working for CSIRO's electronic and mechanical engineering team, I could learn something new and get to be at the core of cutting-edge science, with unique opportunities to pause, reflect, and learn," she said.

We are honoured that CSIRO's Space and Astronomy business unit, which manages the ATNF, received a Silver Pleiades award earlier this year from the Astronomical Society of Australia's Inclusion, Diversity and Equity in Astronomy chapter.

The award recognises organisations with a sustained record of at least two years monitoring and improving the working environment. It also recognises leadership in promoting positive actions as examples of best practice to other organisations in the astronomy community. Read more on our Silver Pleiades award.

In each quarterly edition of ATNF News, we’ll bring you a summary of the new data products publicly available in CASDA, and updates on the progress of ASKAP survey science project datasets.

Current ASKAP survey science project datasets:

Everyone in the astronomy community can now access these data, with data products validated by the teams. For more info visit CASDA.

The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey, or RACS, project is completing multiple surveys of the southern sky covering our ASKAP telescope' full frequency range.

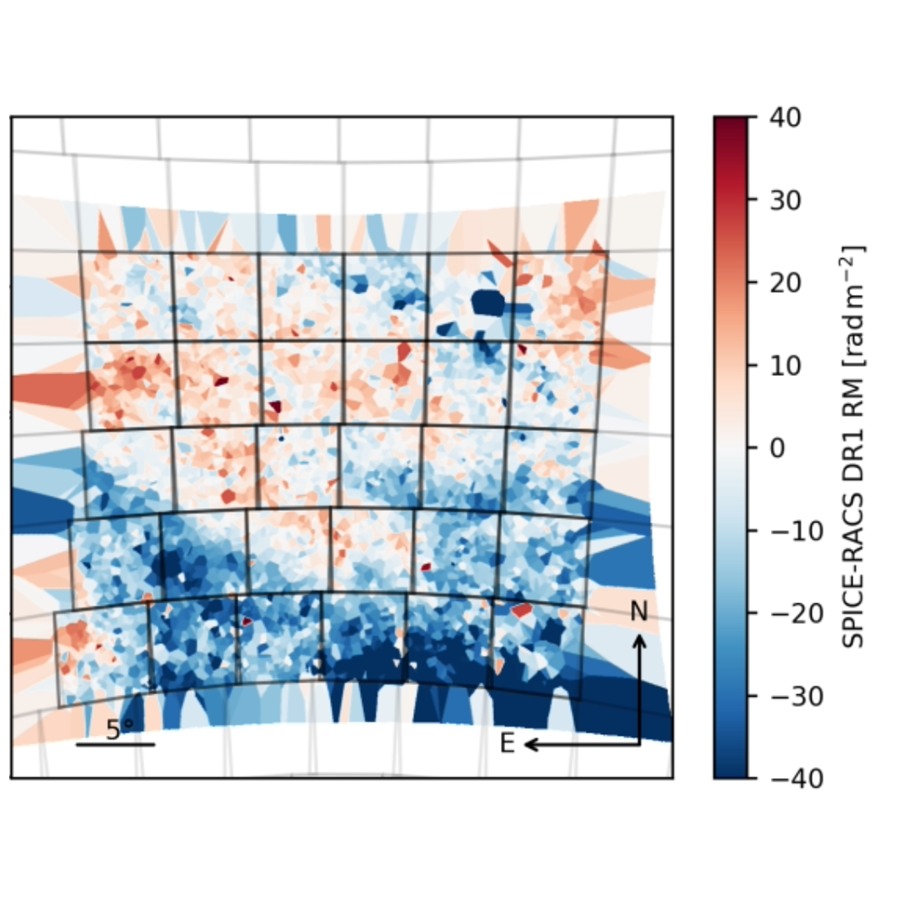

SPICE-RACS (Spectra and Polarisation in Cutouts of Extragalactic sources from RACS) extends the RACS project, and the team behind it is creating a map of polarised sources in the southern sky from RACS data, taking the next step to reveal cosmic magnetism with ASKAP.

The project doesn't create images of the entire sky. Instead, SPICE-RACS efficiently creates small images, called 'cubelets', around each source of radio waves that's identified.

The full set of data products from the SPICE-RACS pilot survey is available on CASDA.