TINY houses are a big attraction in reality television, and it’s not hard to see why when they are cheaper to build and cost less to run than the average house. Going small isn’t everybody’s solution of course, but as electricity prices rise and global warming intensifies, more of us are putting a high price on a few precious stars than ever before.

Energy rating systems are a familiar sight in the 21st century. Whether it’s stuck on a new washing machine or used to advertise a swanky inner city apartment, consumers know it’s important to count their lucky stars to save on power bills.

That ‘star band’ is an easy way for house hunters to know what they’re in for – houses that freeze in winter or roast in high summer are barely worth a star or two, while those that require minimal power to stay comfortable can be certified anywhere up to ten stars.

It’s been nearly twenty years since an energy rating system for Australian houses was first introduced. Back then, the national average was just 1.8 stars. A lot has changed since then thanks to tightened legislation, climbing energy prices, and a more environmentally conscious culture.

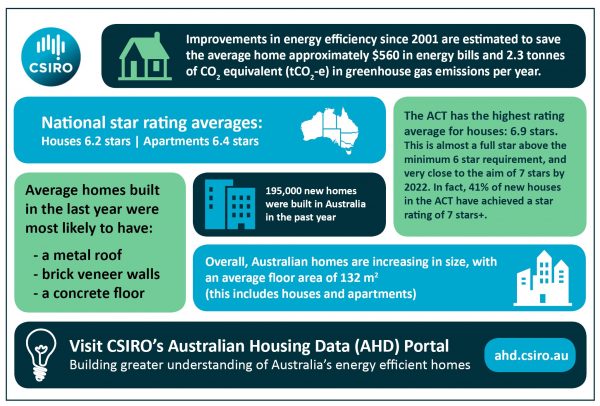

That average has skyrocketed to 6.2, saving more than 2 tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions per house every year, not to mention hundreds of dollars in power savings. To find ways to push savings even further into the green, researchers have been gathering data across the nation to see what makes for a ‘gold star’ performer.

Our state of energy efficiency

In early 2003, national building codes for detached and semi-detached dwellings required power wastage to be kept to a minimum, with new constructions needing to meet an equivalent of around 3.5 to 4 stars. Efficiency standards were tightened further over the next few years and were quickly adopted by all states and territories, with some governments going to greater lengths than others.

The ACT requires all residential sales to declare the property’s energy efficiency rating. Since 2003, property hunters in the nation’s capital can expect to be told if a potential purchase is a power-hungry lemon or an energy bargain.

Property researcher Georgia Warren-Myers from the University of Melbourne recently teamed up with University of Cambridge visiting fellow Franz Fuerst to determine how encouraging sellers to disclose a property’s energy efficiency rating might affect its value.

“We completed a study examining the ACT where a mandatory program has existed for two decades, and found convincing evidence of premiums associated with the star rating scheme for both sales and rental prices,” says Warren-Myers.

For home owners keen to sell, an extra star or two could well be worth the investment for a little extra on the sales price. Properties certified with the mandatory six stars attracted 2.4 percent more on average than properties with just three stars. Go the extra mile and make that seven stars and the premium leaps to 9.4 percent.

There does seem to be a limit, though. Reaching for a rating of eight and above probably won’t pay off, at least not according to the data.

This could simply be the result of a small sample size of properties with exceptionally high ratings, with relatively few willing to push their renovations beyond a certain point. If it’s not, property owners are striking a balance of cost with a desire to appear a little more energy efficient than the neighbours, all to impress buyers.

Some features seem to be prized more than others though. According to Warren-Myers, when it comes to home improvements for a top sale versus a winning rental, we might want different things.

“Interestingly there were stronger premiums found in the rental prices for energy saving or generating features like photovoltaic cells, solar hot water, double glazing, insulation and slab heating,” says Warren-Myers.

“Whilst the sales market valued double glazing and insulation, other factors like photovoltaics and solar hot water were still positive but not significant. Suggesting that perhaps purchasers thought these could be improvements they could make, while the rental market are actively seeking for energy efficient homes.”

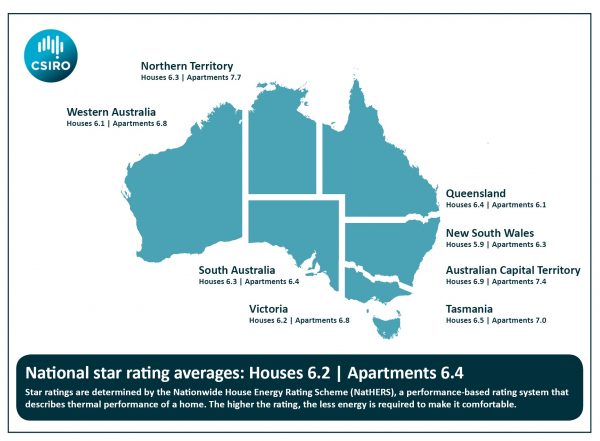

With an average energy rating of 6.9 for houses and 7.4 for apartments, the ACT sets the bar on what we can expect in construction. Across the other side of the country, the statistics aren’t anywhere near as impressive.

“Western Australia seems to lag the national figures,” says CSIRO's Anthony Wright, a lead research consultant for developing models on energy use in houses.

The state’s average energy ratings squeeze in under the national average at 6.1 stars for houses and 6.8 for apartments. Just as it’s hard to confirm the exact causes for ACT’s success based on a single study, the low margin set by WA could come down to a deficit of information more than a weakness in practice.

“We have less data on Western Australia than elsewhere,” says Wright, suggesting that differences in how we measure energy efficiency can make it hard to make a final judgement on performance.

Similarly, subtle differences in the methods and choices of material used can make a big difference in meeting expectations.

“The WA industry is smaller and uses different construction techniques. There is a predominance of double brick,” says Wright.

“This can make it hard to comply with minimum standards.”

A portal to the stars

If having ample data is key to understanding the past and future of energy efficient homes, the CSIRO’s Australian Housing Data portal provides the pathway forward. The online system pools information on energy standards from across the country, painting an evolving picture of design and construction across the years.

“Until the portal was developed it was very difficult to determine how many new houses were exceeding the minimum energy efficiency requirement of six stars,” says Michael Ambrose, a senior experimental scientist at CSIRO.

Thanks to the work of Ambrose and his colleagues, we can now easily visualise the changing face of residential construction through recent years into the future. The portal is the result of raw data gathered through the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS), a program that assesses thermal efficiency of a residence via software fine-tuned to take into account design, construction, and needs imposed by the local climate. It’s not the only way to assess a home’s heating and cooling, but by using trained NatHERS accreditors you’re guaranteed to meet the standards required by the national construction code.

For home owners, an accreditation provides a convenient yard stick showing how their home or apartment’s mix of energy efficiency measures tallies against a standard. For researchers, thousands of measurements describe an even bigger picture.

“We would be asked ‘how many homes achieve seven stars?’ and we could not give an answer until now,” says Ambrose.

“Also, questions about the size of houses and the use of double glazing have been ones that we were often asked and can now answer.”

Based on more than NatHERS Certificates from more than 110,000 residences across the states and territories, we can now tell our fascination with tiny homes isn’t matched by our tastes. Since 2016, the average floor area for new dwellings has grown by several square metres. Still, that little extra room to move is more than being matched by investments in energy saving materials and features.

According to Ambrose, sharing those energy saving tricks is what will continue to push the limits on what we can achieve. Affordable materials and measures are there; it’s a lack of awareness, says Ambrose, that creates the impression that there’s no demand.

“If we had the public demanding higher performance houses then the industry would deliver,” says Ambrose.

“This is what has happened in the commercial building space with clients demanding and getting buildings that are well above the minimum regulatory requirements.”

Australia has a long way to go when it comes to energy use. We can aim for the stars but, like charity, environmental responsibility begins at home.