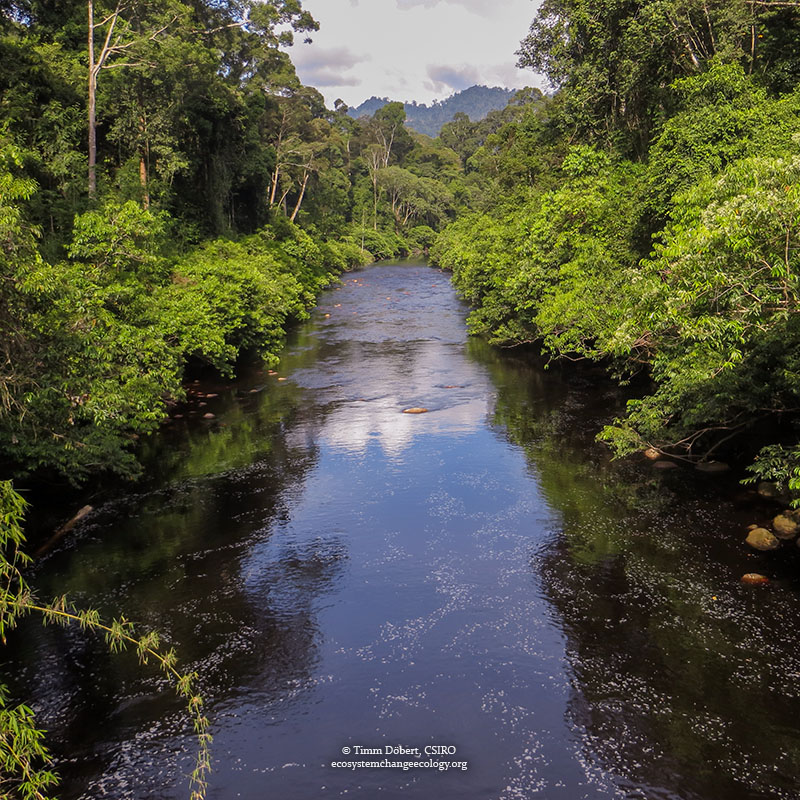

CUT in half by the equator, the island of Borneo is a global hotspot of biological diversity. Evolved over 140 million years, its ancient lowland rainforests are exceptionally complex ecosystems, sustaining the world’s tallest tropical rainforest trees, and a wealth of extraordinary lifeforms including more than 12,000 species of flowering plants.

My PhD journey started deep in the heart of this mysterious wilderness.

My studies were investigating human impacts on these lowland rainforest ecosystems. I was enrolled at the University of Western Australia[Link will open in a new window] and with the Ecosystem Change Ecology[Link will open in a new window] team at CSIRO[Link will open in a new window]. However, the majority of my time was spent with an international team of researchers at the Stability of Altered Forest Ecosystems (SAFE) project[Link will open in a new window] in Malaysian Borneo.

Borneo’s lowland rainforests have been radically transformed over the past century, first through rampant exploitation of commercially valuable Dipterocarp trees, and more recently due to the rapid expansion of oil palm plantations. As a result, few areas with intact primary rainforest remain and scars of the human footprint are all too evident.

The island is now carved up by a vast labyrinth of no less than 270,000 km of roads and oil palm monocultures, in many areas stretching as far as the eye can see. To better understand the ecological implications of past logging activities and the long-term consequences of forest to oil palm conversions, the SAFE project was provided with the unique opportunity to undertake scientific research ahead of an imminent forest-to-oil palm transformation.

For nearly three years a basecamp in the rainforest became my treasured home. Modern-day luxuries were reduced to a bare minimum, a life in nature completely detached from the trappings of city life. Sleeping arrangements consisted of simple wooden frames with a tarp roofing that would regularly succumb to the forces of nature, and rows of hammocks providing little privacy. The camp was rounded out by a small kitchen area with portable gas stoves, a generator to deliver few hours of electricity at night, work spaces that provided little shelter from the elements.

The majority of the people staying in our forest camp were local research assistants, including Roy and Mamat who worked alongside me throughout my PhD studies. Their excellent knowledge of the Bornean flora would play a pivotal role in the success of our project.

As part of the large SAFE project linking teams from all over the world, our component of the research focused on plant community changes across a logging-intensity gradient. We established nearly 600 vegetation plots throughout a human-modified landscape, from primary to repeatedly-logged forest as well as different-aged oil palm plantation sites. To get to some of those field sites, we would have to trek for hours through trackless and often impenetrable forest, walk up rivers and climb steep hillslopes. We fought through punishing humidity and torrential downpour, soaking our clothes in sweat and rain, our bodies scarred from heavily-armed vegetation, and under constant attack from blood-thirsty creatures, such as tiger leeches and horse-flies.

In the late afternoon, we would return with heavy bags loaded with precious plant and soil samples, for immediate processing and drying in custom-made field ovens. Once dry, biomass samples were taken to the lab in the Maliau Basin Conservation Area (MBCA)[Link will open in a new window] for further processing by local helpers Nadya and Onassis, while reference samples were sent to the Forestry Department in Sandakan[Link will open in a new window] for species identification.

In close collaboration with the Sandakan Herbarium, we built an extensive database of at least 838 plant species across 437 genera and 125 families. These plant data were then used to quantitatively explore the influence of logging on the taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity of understorey plant communities as well as the relationship between logging and exotic plant invasions. Plant invaders often take advantage of anthropogenic habitat disturbance and the enormous global network of roads, both of which increasingly threaten the few remaining wilderness areas of the planet.

Overall, we found a strong logging signal in both functional trait and phylogenetic diversity including a significant logging ‘threshold’ effect at approximately 65 per cent forest canopy loss (Döbert et al. 2017a, JEcol[Link will open in a new window]). In addition, our results showed relatively low current levels of invasion by exotic plants, despite an intensive logging history and widespread occurrence of logging roads (Döbert et al. 2017b, Biotropica[Link will open in a new window]). Nevertheless, we revealed concerning trends, such as a strong positive relationship between logging and exotic plants, as well as a broad distribution of the pantropical invader Clidemia hirta.

Looking back, the thrill of spotting remarkable wildlife made up for any hardship associated with life under such challenging conditions. In the early morning hours, I would wake to the whooping calls of the gibbons reverberating through the valleys and listen to the majestic wingbeat of the hornbills, before taking a bath in the nearby stream to the sight of foraging orangutans.

At night, I would venture into the forest in search of its nocturnal dwellers. It is at night that the forest reveals its magnificent colours and smells, the subtle nuances in the shades of green in the leaves reflecting the remarkable diversity in trees, their flowers fully opened to welcome the armada of insect pollinators. Setting foot into the gloom of a tropical rainforest, time seems to stand still, and one immediately feels at peace with the world around, body and mind refreshingly alive, the senses sharpened and on constant alert, prepared for the encounter of a lifetime.

Most nocturnal mammals give themselves away with the glint of light from the reflective tissue in their eyes. Equipped with torches and camera, I searched the forest floor and canopy for those reflections, in hope of getting a glimpse of one of those elusive species rarely observed let alone caught on camera. Driven by this curiosity and lots of luck, I eventually found an impressive array of fascinating creatures, including western tarsier, slow loris, banded linsang, clouded leopard and many more.

Our research contributes to the growing literature on the ecological implications of tropical land use change on biodiversity values and ecosystem functioning. Specifically, we provide new insight into the myriad of ways that logging can impact on plant communities in tropical rainforests.

It is my hope, that our global community will take on this grand challenge of safeguarding the remaining lowland tropical rainforests, so that future generations will be able to discover and marvel about this astounding celebration of life, just as I was privileged to do.

Read more about Timm Döbert[Link will open in a new window]'s work in the Journal of Ecology blog[Link will open in a new window].

Please refer any requests for permission to reuse images to bruce.webber@csiro.au.