Key points

- Both art and AI have moved from relying on domain-specific, physical models to the recognition of patterns.

- Throughout history, technology has greatly disrupted both art and AI.

- New forms of generative AI are impressive, but pose numerous ethical, legal and philosophical challenges.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has made remarkable progress creating images that are not only breathtaking, but astonishingly diverse in style. Ten years ago, such an achievement would have been deemed unlikely by experts. Today, AI can create images using specific artistic styles, such as Van Gogh’s unique approach, with an infinite range of variations.

This raises an intriguing question. How can a series of instructions running on a computer produce art that rivals human creativity?

Art history and AI

Examining the similarities between the evolution of AI and art history may provide some answers.

The history of modern science can be characterised by the development of specific models that represent the world. Traditional models are developed using mathematical equations, physics, and logic. For example, Newton’s law describes how gravity works with a very simple formula.

However, modern AI has become increasingly reliant on generic models that can learn complex relationships from vast datasets. They do this without encoding explicit knowledge (so-called artificial neural networks). These new models do not rely on physics or complex mathematical equations but rather are built by layering many small computation units. Taken as a whole, these can learn and reproduce any pattern present in the data.

Interestingly, the evolution of art mirrors that of AI in many ways. Art has also undergone a significant transformation, from being rooted in explicit knowledge and classical traditions, to embracing approaches that challenge the boundaries of art itself.

Like AI, art has evolved to incorporate a more organic and intuitive approach that emphasises the discovery and creation of new forms and styles.

The era of building accurate models

For decades, constructed AI models relied upon analytical solutions and equations. These were defined by a handful of meaningful parameters crafted by human experts. The primary objective of this early iteration of AI was to adjust those parameters to explain experimental data.

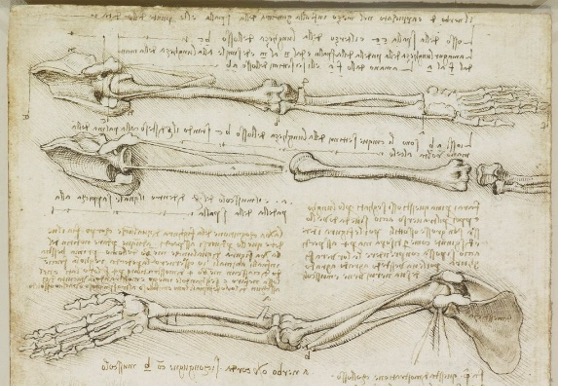

Artists also used models and adapted them to represent what they observed. Their models came from the careful study of anatomy, colour and shape. For example, during the Renaissance, da Vinci dedicated himself to studying the human form by performing dissections of humans and animals. He constructed a mental model of what a human body should look like, which was then used to accurately reproduce characters or imagine allegorical religious paintings.

In 2004, anatomy professors Massimo Gulisano and Pietro Bernabei used computers to analyse Michelangelo’s David, confirming the extreme anatomical accuracy of the sculpture (except for a missing muscle that upon investigation was due to the stone imperfection).

These mental models became more sophisticated during the turn of the 16th century, with artists perfecting the texture and vibrancy of fabrics, water, and light.

The data-driven era

With advances in computing, new methods emerged allowing AI to recognise sophisticated patterns in large datasets. A watershed moment occurred in 2012 when computer scientists trained a large, deep convolutional neural network to recognise the content of images. It outperformed existing methods by a wide margin. The research community suddenly realised the potential of data-driven approaches.

Ever since, increasingly complex models are learning more sophisticated patterns from increasingly large datasets. It seems there is no end to what enough data and a large model can achieve with enough resources.

In the 19th century, artists began painting what they saw, refusing to be constrained by the subject giving rise to the Impressionist art movement. This is much akin to a data-driven approach: reproduce the data (observed scene) without trying to use models of the subject matter.

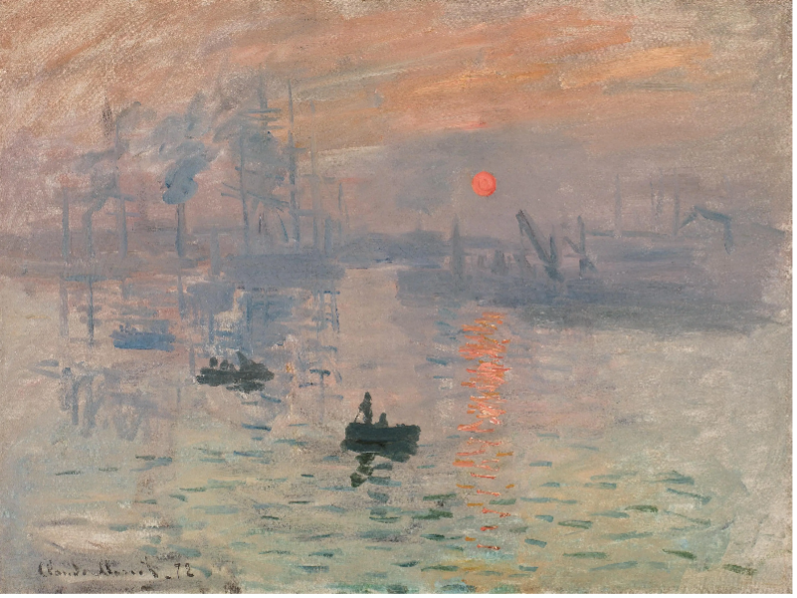

In 1874, Claude Monet’s defining Impression, Sunrise was exhibited in Paris. It was mocked by art critics as a personal ‘impression’ rather than a realistic representation of the scene in question.

This was the seed of the Impressionism movement and is often considered a watershed moment in art history. Others soon realised how powerful art could be when the constraints of realism were lifted.

The reason for this evolution

While the internet and advanced computing disrupted AI, technology also disrupted the art world.

For art, it was photography. Until the 19th century, the only way to produce an image was through the work of artists. There was a huge demand for immortalising events, individuals, or places.

By the end of the 19th century, photography was good enough to meet that demand and art was disrupted. Art evolved to produce “impressions” or abstract pictures, leaving the job of documenting reality to photographs.

The modern era

The evolution of art is reflected even today in how drawing is taught.

One approach is drawing only what one sees, without reference to any model, which is deceptively challenging. A second involves studying anatomy, basic shapes, and how light interacts with forms, so one can draw a model using the scene merely as a reference and not as something to reproduce accurately.

Over time, artists blend these techniques, with others, to develop their personal approaches. However, the duality between model-based and data-driven approaches remains clear and ever-present.

For example, many artists endeavour to identify the essence of things or emotions, a technique well-illustrated by Picasso’s bull study. This is a key theme in AI, which reduces the complexity of very large models to identify the core architecture, generating the simplest possible model.

As methods have mixed in the modern art world, so too have many scientists pushed for a mixed approach to AI that infuses data-driven models with symbols and physics. The aim is to strike a balance between the interpretability of symbolic AI and the scalability and power of data-driven methods.

By combining these techniques, researchers hope to create more robust and adaptable AI systems that can manage complex and diverse real-world problems.

Meanwhile, the arts continued to build on Impressionist freedom. This resulted in an explosion in techniques and movements throughout the 20th century that continues unabated to this day.

This is not dissimilar to the way modern AI systems can create realistic and beautiful images.

Patterns in images can be learnt by AI, and patterns of those patterns, to such an extent that any image can be understood as a hierarchical assemblage of patterns. All arising from a vast library that the AI system has learnt.

The era of generative models

Fast forward to 2023, and generative AI methods have been developed to assemble patterns in new ways to create never before seen images. The selection and ways these patterns combine are informed by prompts. These can range from human-defined text prompts, rough sketches and sound to even the motion of a crowd, as in the case of Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised. The AI-driven digital display constantly creates a new picture depending on the location of the viewers.

While generative AI art is undoubtedly impressive, it poses numerous challenges. These include copyright ownership, deep fake images and videos, and AI-generated pieces swamping art websites with an infinite supply of new works.

Moreover, this technology raises deeper questions about the nature of creativity and human experience.

As we witness a world increasingly dominated by AI-generated art, we must wonder whether anything new can ever be created again or whether what we consider as new art is merely an unlikely and interesting random fluctuation that happens to resonate with us. After all, what humans generate is often a complex collection of experiences and existing pieces assembled in new and innovative ways.

While the ability of AI to create art that rivals human creativity remains a subject of debate, the evolution of AI and art share remarkable similarities.