Hydrogen (H2) is a naturally occurring gas in the atmosphere and, although it is not a greenhouse gas, plays an important role in climate chemistry. Like methane, it reacts with a key “cleaning” molecule, which can indirectly increase the warming potential of methane, and other climate-relevant gases such as ozone (pollution) and water vapor.

Interest in hydrogen has increased in recent years due to the potential expansion of a hydrogen-based energy system as part of global decarbonisation strategies. Hydrogen is widely used today in ammonia production, oil refining, and chemical manufacturing, and is increasingly promoted as a low-carbon energy carrier for industry, transport, and energy storage.

The Global Hydrogen Budget, produced under the umbrella of the Global Carbon Project, is led by Stanford and Auburn Universities, along with CSIRO and 25 other international research institutions. It shows that rising hydrogen concentrations since 1990 have intensified climate change and amplified methane's impact on global warming.

How does hydrogen warm the climate if it is not a greenhouse gas?

Hydrogen in the atmosphere reacts with methane, ozone (a pollutant), and water vapor in ways that lead to global warming, even though hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas.

A key pathway by which hydrogen warms the climate is by consuming the same cleaning molecule, hydroxyl radical (OH), that oxidizes methane. By competing for the same cleaning molecules, additional hydrogen in the atmosphere will extend how long methane remains in the atmosphere, leading to increased global warming.

When we put together all the hydrogen atmospheric warming feedbacks (with methane, ozone, and water vapor), hydrogen has an indirect global warming potential 37 times more powerful than carbon dioxide on a 20-year timeframe, and 11 times more powerful over 100-year timeframe.

Hydrogen in the atmosphere is on the rise due to human activities

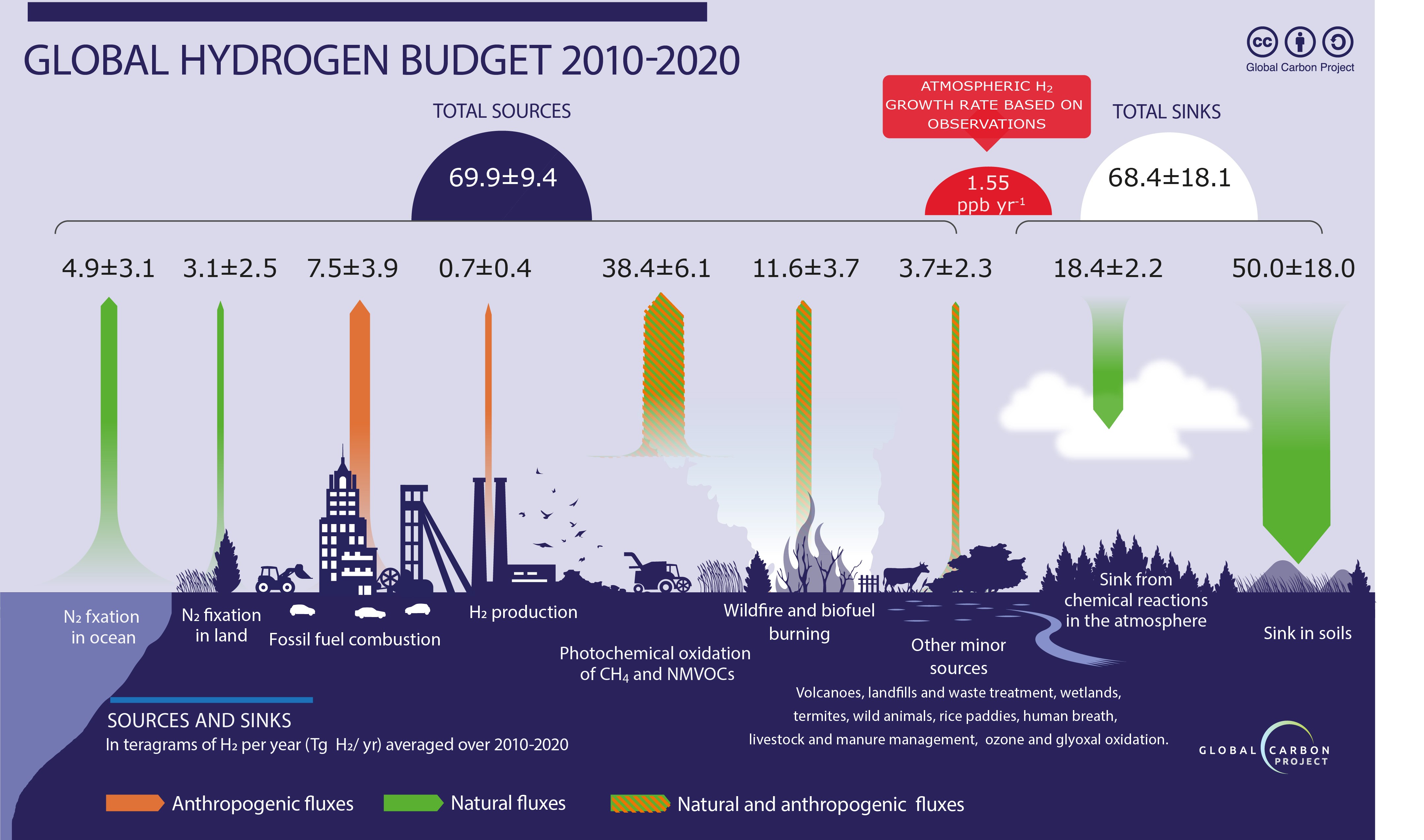

Concentrations of hydrogen in the atmosphere have increased over the last three decades. Hydrogen is produced through a combination of natural sources, including oxidation of natural methane and other hydrocarbons, biomass burning, and biological processes, as well as human activities such as fossil fuel use, industrial processes, and leakage from hydrogen production, storage, and transport.

Despite the mix of natural and anthropogenic emission sources, the observed increase in atmospheric hydrogen is largely attributable to human activity.

The largest contributor is the increase in methane emissions (their oxidation of) from livestock, the natural gas industry, coal mines, and landfills. However, direct emissions from industrial activities are cleaner today than they were previously due to increased combustion efficiency. Leakage from hydrogen production has increased, but its contribution to the total is currently small.

Other emissions from human activities include those from nitrogen-fixing agricultural crops such as soybeans, common beans, and alfalfa. Fires, human-initiated and natural, are important contributors to hydrogen emissions but are not yet contributing to the observed global trend.

The budget found that 70 per cent of all emissions are removed by the natural hydrogen soil sink, largely through bacteria that consume hydrogen as an energy source, and another portion is removed through oxidation in the atmosphere. However, these sinks are insufficient to counteract the rise in atmospheric hydrogen.

Future hydrogen emissions and additional warming

It is not known how widely hydrogen will be adopted in future global energy systems.

This study took the various levels of hydrogen utilisation from scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). To these scenarios, a range of possible leakage rates was added, from a tight hydrogen economy (1 per cent leakage) to a very leaky hydrogen economy (10 per cent leakage).

The feedbacks between hydrogen leaks and anthropogenic methane emissions show that the mean global surface temperature could increase by an additional 0.01 to 0.05 °C. Although the warming appears small, this amount is equivalent to 1 to 3.5 times the warming produced by the cumulative greenhouse gas emissions of Australia since 1850.

Supporting a sustainable hydrogen economy

Producing hydrogen via electrolysis powered by renewable energy can play an important role in the future of the global energy system. However, producing hydrogen from natural gas as a feedstock (as most hydrogen is currently produced) could offset the climate benefits of hydrogen, if methane leaks occur, given its high global warming potential (86 times that of carbon dioxide over a 20-year timeframe).

Putting in place controls on leakage in the supply chain for hydrogen production, transport, and utilisation will minimise emissions to the atmosphere. That is, to design systems for leak detection and repair.

Reducing methane emissions from human activities such as extraction, transport, and utilisation will lower atmospheric hydrogen concentrations and, in turn, indirectly reduce hydrogen-induced warming. The replacement of methane feedstocks for clean hydrogen produced by splitting water with renewable energy will have this indirect benefit.

These results underscore the need for a deeper scientific understanding of the global hydrogen cycle and its links to global warming to support a sustainable hydrogen economy.

Hydrogen (H2) is a naturally occurring gas in the atmosphere and, although it is not a greenhouse gas, plays an important role in climate chemistry. Like methane, it reacts with a key “cleaning” molecule, which can indirectly increase the warming potential of methane, and other climate-relevant gases such as ozone (pollution) and water vapor.

Interest in hydrogen has increased in recent years due to the potential expansion of a hydrogen-based energy system as part of global decarbonisation strategies. Hydrogen is widely used today in ammonia production, oil refining, and chemical manufacturing, and is increasingly promoted as a low-carbon energy carrier for industry, transport, and energy storage.

The Global Hydrogen Budget, produced under the umbrella of the Global Carbon Project, is led by Stanford and Auburn Universities, along with CSIRO and 25 other international research institutions. It shows that rising hydrogen concentrations since 1990 have intensified climate change and amplified methane's impact on global warming.

How does hydrogen warm the climate if it is not a greenhouse gas?

Hydrogen in the atmosphere reacts with methane, ozone (a pollutant), and water vapor in ways that lead to global warming, even though hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas.

A key pathway by which hydrogen warms the climate is by consuming the same cleaning molecule, hydroxyl radical (OH), that oxidizes methane. By competing for the same cleaning molecules, additional hydrogen in the atmosphere will extend how long methane remains in the atmosphere, leading to increased global warming.

When we put together all the hydrogen atmospheric warming feedbacks (with methane, ozone, and water vapor), hydrogen has an indirect global warming potential 37 times more powerful than carbon dioxide on a 20-year timeframe, and 11 times more powerful over 100-year timeframe.

Hydrogen in the atmosphere is on the rise due to human activities

Concentrations of hydrogen in the atmosphere have increased over the last three decades. Hydrogen is produced through a combination of natural sources, including oxidation of natural methane and other hydrocarbons, biomass burning, and biological processes, as well as human activities such as fossil fuel use, industrial processes, and leakage from hydrogen production, storage, and transport.

Despite the mix of natural and anthropogenic emission sources, the observed increase in atmospheric hydrogen is largely attributable to human activity.

The largest contributor is the increase in methane emissions (their oxidation of) from livestock, the natural gas industry, coal mines, and landfills. However, direct emissions from industrial activities are cleaner today than they were previously due to increased combustion efficiency. Leakage from hydrogen production has increased, but its contribution to the total is currently small.

Other emissions from human activities include those from nitrogen-fixing agricultural crops such as soybeans, common beans, and alfalfa. Fires, human-initiated and natural, are important contributors to hydrogen emissions but are not yet contributing to the observed global trend.

The budget found that 70 per cent of all emissions are removed by the natural hydrogen soil sink, largely through bacteria that consume hydrogen as an energy source, and another portion is removed through oxidation in the atmosphere. However, these sinks are insufficient to counteract the rise in atmospheric hydrogen.

Future hydrogen emissions and additional warming

It is not known how widely hydrogen will be adopted in future global energy systems.

This study took the various levels of hydrogen utilisation from scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). To these scenarios, a range of possible leakage rates was added, from a tight hydrogen economy (1 per cent leakage) to a very leaky hydrogen economy (10 per cent leakage).

The feedbacks between hydrogen leaks and anthropogenic methane emissions show that the mean global surface temperature could increase by an additional 0.01 to 0.05 °C. Although the warming appears small, this amount is equivalent to 1 to 3.5 times the warming produced by the cumulative greenhouse gas emissions of Australia since 1850.

Supporting a sustainable hydrogen economy

Producing hydrogen via electrolysis powered by renewable energy can play an important role in the future of the global energy system. However, producing hydrogen from natural gas as a feedstock (as most hydrogen is currently produced) could offset the climate benefits of hydrogen, if methane leaks occur, given its high global warming potential (86 times that of carbon dioxide over a 20-year timeframe).

Putting in place controls on leakage in the supply chain for hydrogen production, transport, and utilisation will minimise emissions to the atmosphere. That is, to design systems for leak detection and repair.

Reducing methane emissions from human activities such as extraction, transport, and utilisation will lower atmospheric hydrogen concentrations and, in turn, indirectly reduce hydrogen-induced warming. The replacement of methane feedstocks for clean hydrogen produced by splitting water with renewable energy will have this indirect benefit.

These results underscore the need for a deeper scientific understanding of the global hydrogen cycle and its links to global warming to support a sustainable hydrogen economy.